Here's a fascinating bit of history for today from the The Writer's Almanac. (Text from The Writer's Almanac; photos from archives.) Guess we'd better not get too smug about the balmy March days we've been having. You never know.

Today is the anniversary of the Great Blizzard of 1888, a storm that dumped up to 50 inches of snow along the East Coast from Montreal to Washington, D.C. Four hundred people died in the storm, more than 200 of them from New York City, which was hit particularly hard.

Most storms in the Northeast begin with a cold air mass, often centered over New England, but this time that didn't happen. The days before the storm were mild, with temperatures in the 40s and spring seemingly just around the corner. Two days before the storm was a warm and sunny Saturday, and New Yorkers walked outside, enjoying the greening grass and budding trees. They went shopping or lined up for the opening Barnum & Bailey Circus parade in Manhattan. Sunday March 11th was overcast, with a midday temperature of 42 degrees. The U.S. Army Signal Corps in Washington, D.C., was the go-to weather service, and they were closed on Sundays to observe the Sabbath. However, they had left behind their weather prediction for the coming days: "Fresh to brisk winds, with rain, will prevail, followed by colder brisk westerly winds and fair weather throughout the Atlantic states."

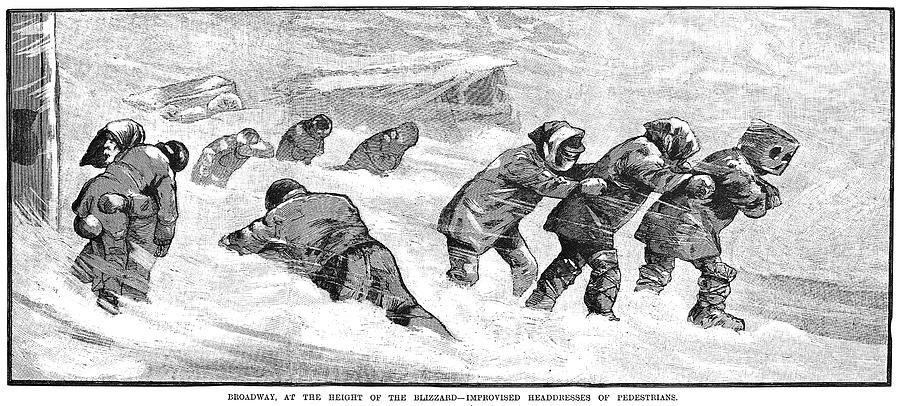

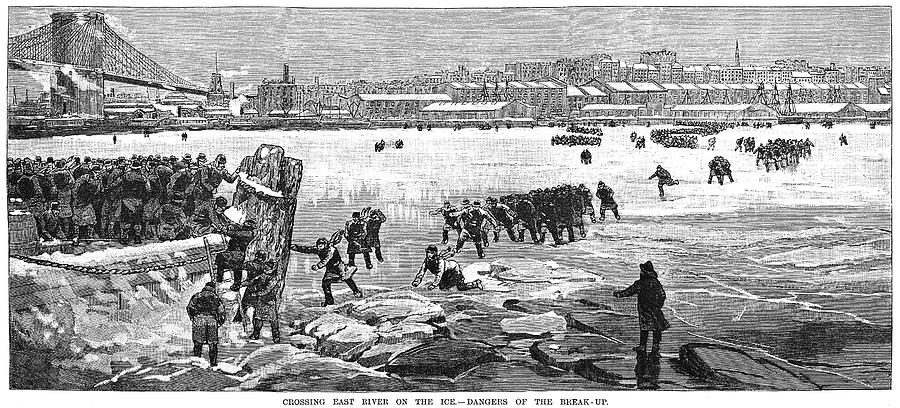

On Sunday afternoon, the rain came and the temperature slowly began to drop. It reached freezing just after midnight, and the rain turned to snow. The wind speed rose, with gusts of up to 80 mph. By Monday morning, everything in New York City was chaos. Walking in the snow and wind was dangerous, and all trains stopped - one derailed and killed several people. Debris flew through the air. By evening, the temperature was in the single digits. The city's 6,900 electric lines all stopped working, so no one had telephone or telegraph access. Fancy hotels filled their lobbies with cots for stranded civilians. All stores were closed, mail was stopped, and the city was more or less shut down. The snow drifts were up to 20 feet high, and many of the people who died in the storm were found buried in them. The East River was so blocked with ice that thousands of people treated it like a bridge and walked right across between Brooklyn and Manhattan. After the police realized what was happening they started blocking pedestrians, fearing more deaths.

In its account of the blizzard on March 13th, The New York Times noted that the day before, the usual morning vendors had been missing: milkmen, newspaper boys, and bakers. The reporter wrote: "Thackeray says that it is the small ills of life that worry the most, and probably thousands of New-Yorkers yesterday morning - good, steady churchgoing heads of families when they had to get through their breakfasts without their favorite newspaper, their hot buttered roll, and their fragrant coffee enriched with the boiling milk began to seriously question whether life was worth living after all, with all those trials and tribulations to undergo."

The Great Blizzard of 1888 caused some huge infrastructure changes in New York City. The above-ground electric lines, gas and water lines, and transit rails not only failed to work during the storm, but they also became a liability, with lines flying through the air, electricity exposed directly to snow and water, and trains derailing. Immediately after the storm, the New-York Tribune wrote an article pressing for a below-ground subway, and the city formulated a plan a few years later.

We do not want a repeat.

ReplyDelete